Krystyna Ziach

kunstinzicht.nlRubrieken

Over het werkFluid Time / Krystyna Ziach 2021-2023Krystyna Ziach’s Spaces of Sculptural Imagination, text by Christian Gattinoni, chief editor of lacritique.org 2015Space of Imagination / Krystyna Ziach, book, text by Hans Rooseboom, curator of photography at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2014Krystyna Ziach, Marged Disciplines, text by Hans Rooseboom, curator of photography at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2014Dark Street Revisited, 2013Work of Krystyna Ziach in collection of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2012Ephemeral Library 2010-2018Into the Void 2010-2017Inner Eye / Krystyna Ziach, by Joanne Dijkman, 2008Infinity & Archê/ Krystyna Ziach, book texts by Flor Bex, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Muhka Antwerp, 2006The Elements of Existence / Krystyna Ziach - ARCHÊ, by Cees Strauss, 1996Archê - The Ambivalence of Water and Fire / Krystyna Ziach, by Mirelle Thijsen, 1996Krystyna Ziach - Where Emotion Meets Reason, by Cees Straus, 1994A Chamber of Mirrors, text by Reinhold Misselbeck, curator of photography & new media of the Ludwig Museum, Cologne, 1994A Garden of Illusion / Krystyna Ziach, 1993, text by Iris DikOuter Space / Krystyna Ziach, text by Alexandra Noble, curator of the South Bank Centre in London,1991Melancholy / Krystyna Ziach - Drama Between Ratio and Emotion, text by Mirelle Thijsen, 1990Japan / Krystyna Ziach, by Huib Dalitz, a former director of the Foundation of Visual Arts Amsterdam, 1988Krystyna Ziach / Metamorphosis, text by Gabriel Bauret, Camera International, 1986, Paris

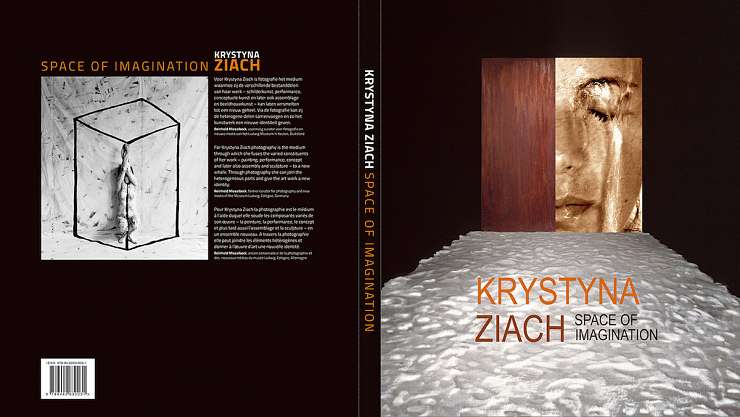

Book, text by Hans Rooseboom, curator of photography at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam & Jan Teeuwisse, director of the Museum Beelden aan Zee in The Hague, NL, 160 pages, bound, published by Waanders & De Kunst, NL, in 2014 at the occasion of the solo exhibition Space of Imagination at the Museum Beelden aan Zee, The Hague, NL, 2014-2015

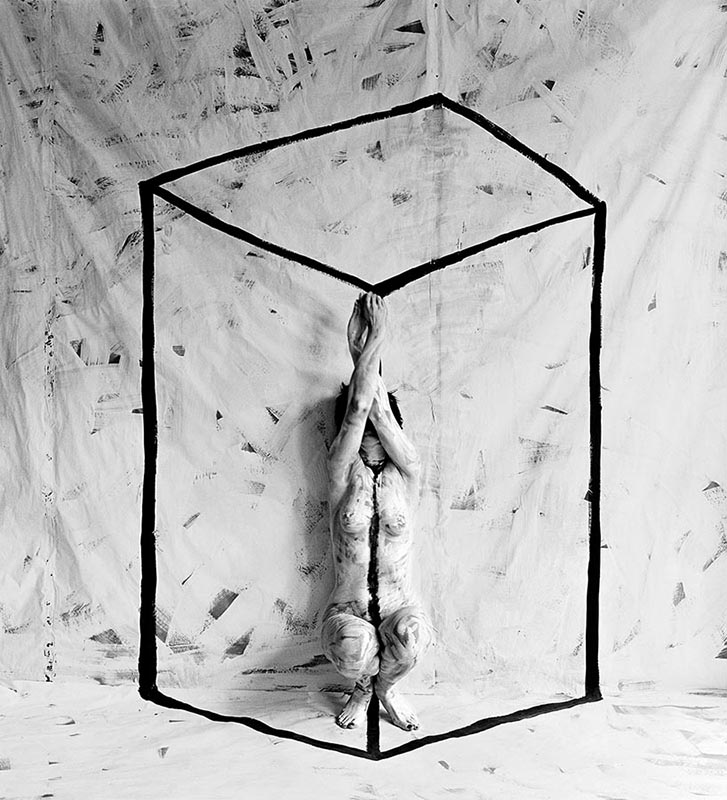

Krystyna Ziach is the kind of photographer who constantly perceives images in the environment she is in at the moment. The kind of photographer who has ‘seen’ the photograph on her retina before having made the actual shot. The kind of photographer who perceives a different meaning in an object than other people, e.g. the photograph ´Imperial Gardens I´ which is part of the series ´Infinity´ she made in 2002-2003. We see the long, horizontally growing branches of a number of trees that are supported by posts. They resemble caryatids, the sculptures of women used as pillars, as decorative supports, in antiquity. In all their bare simplicity these posts are much less conspicuous, elegant or venerable than the tree branches they support, yet Ziach has portrayed them in her photograph in such a way that they suddenly draw as much attention. Finally. With their bolt upright vertical position they contrast with the horizontal growth of the branches. It is true they may -literally- have an entirely subservient, subordinate, supportive function, yet for once they are of equal value. It is typical of Ziach’s intellectual versatility and visual capabilities that she not only perceives this, but also convincingly transforms it into an image. Krystyna Ziach has not from the start devoted herself to photography. Between 1974 1974 and 1979 she studied sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts of Cracow, the city where she was born in 1953. She continued her education in the Netherlands at the Academy of Fine Arts AKI in Enschede. This establishment had a good reputation in the field of training photographers with an artistic eye and it was there that Ziach turned to photography and video. She has been successful in using these two media ever since, though without ever disavowing her background as a sculptress. As she once put it herself, her education in sculpture formed her way of looking at things. Even after applying herself to photography, she has always continued to look at reality like a sculptress. This too is apparent in a photograph such as ´Imperial Gardens I´. The images she perceives even before having transformed them into an artwork, are not only photographic images (pictures) but also sculptures. By their severe simplicity the caryatid-like posts are reminiscent of modern sculpture. In the body of work Ziach created since the early eighties, she made several photographs which not only show her intimacy with sculpture, but also with other art forms. A triptych painted by Francis Bacon, an engraving by Albrecht Dürer, the black cross by Kazimir Malevich: they all were sources of inspiration. In her studio she played a refined game of naked figures within a painted setting. In a number of these photographs she made use of a mirror, e.g. in ‘Odalisque’ and ‘Irrational Space’, both from 1989. In art -and meanwhile also in photography- the mirror is a classical motif. It is also a classical means to represent the play between two and three dimensions, between seeing someone else or yourself, between painted and photographed, real and unreal, direct or mirrored.The photo works ‘Odalisque’ and ‘Irrational Space’ made in 1989 can be seen as the prelude to a new phase in Ziach’s work, since sculpture returned in her work in the nineties. She begins to use photographs as elements of three-dimensional objects. In works such as ‘Infinity’ (1991) and ‘Illumination’ (1992) we see the mirror motif again, yet now not as part of a photograph, i.e. of a two-dimensional object, but as an element of a three-dimensional sculptural work. Photography is an ‘ingredient’ of the works she started to make as of the early nineties. She characterized these new works herself as photo sculptures incorporated in monumental spatial installations. Hence no photographs of sculptures, but photographs that are sculptures themselves, or are at least part thereof. The photographic images commence an interaction with the geometrical form of their frames and -as things are wont to go in sculpture- with the environment. Where she used mirrors, as in ‘Infinity’ and ‘The Curtain of Pleasure’ (1992), this interaction is of course enhanced. In that case the environment contributes to what a photo sculpture looks like. A triangle can manifest itself in different ways: containing a mirror (‘Infinity’) or a photograph (‘Illumination’), or it can be reduced to two dimensions (as in ‘Odalisque’ and ‘Irrational Space’). Krystyna Ziach shows us how prolific the cross-fertilization of different media can be, media which have been used strictly separately for a long time, having their own status, effect and scope. Engraving and painting are two old, familiar and renowned art forms, having held a high position in the hierarchy of artistic techniques for centuries. Sculpture had to wait a bit longer for this undivided recognition, whereas photography has only recently, say fifty years ago, been accepted for the first time by the art world. Then the photographer was no longer a mere provider of ‘snapshots’, but photography was regarded as a means or technique with serious artistic possibilities. As of the sixties many visual artists also ‘ventured on’ photography. Some left it at a short flirtation, for others it developed into a long-lasting, close commitment. As a consequence photography also played an increasingly important part at art academies. The AKI, where Krystyna Ziach finished her education, is only one case in point. At the time she studied there, it was no longer a chutzpah to want to make art using photography (and video). Looking in retrospect at the work made by Krystyna Ziach since the eighties, we can conclude that she did not renounce her first love, sculpture, but on the contrary contributed to bringing the match between photography and sculpture closer. In many of her works one cannot do without the other. When Ziach began to devote herself to photography, she started relatively modestly, with works that were in the first place distinct photographs, even though she played with depth and shallowness and was inspired by painting, engraving and sculpture. After subsequently, in the nineties, making the afore-mentioned photo sculptures, with photography and sculpture playing an equal part, she made as from the year 2000 a number of works which are again in the first place photographs, images in a plane. The sculptural element is unmistakable though. She calls them herself sculptures which she discovers (sees) in culture, nature and industry. ‘Imperial Gardens I’ is one example. In 2013 she returned to that photograph and turned it into a diptych. On the right part a female figure has suddenly appeared who can only be a caryatid: with her arms raised she (seemingly) supports one of the tree branches. The human being, nature and culture have become one, and so have photography and sculpture.

Translation : Hanny Keulers

This book has been included in many world's libraries a.o.: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Koninklijke Bibliotheek The Hague, Tate Museum London, Bibliothéque Kandinsky-Centre Pompidou Paris, Institut national d'histoire de l'art Paris FR, Harvard University Cambridge US, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York US, Columbia University Libraries New York US, New York University US, Princeton University Library US, Library of Congress Washington US, Cleveland Museum of Art US, Art Institute of Chicago US, University of Chicago Library US, Museum of Fine Arts Houston US, Stanford University Libraries US, Getty Research Institute Los Angeles US, MoMA New York US, University of Pennsylvania Libraries Philadelphia US, University of Michigan Ann Arbor US, University of Toronto Canada, Museum Kunst Palast Dûsseldorf DE, Museum of Contemporary Art MuHKA Antwerp BE, Middelheimmuseum Antwerp BE, Kunsthaus Zürich CH, Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte München DE, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin DE, Sächsische Landesbibliothek Dresden DE and others.

Toned gelatin silver print, 47,5 x 45,5 cm

Metamorphosis 1983-1986

Collections : Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Musée de la photographie, Charleroi, BE

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

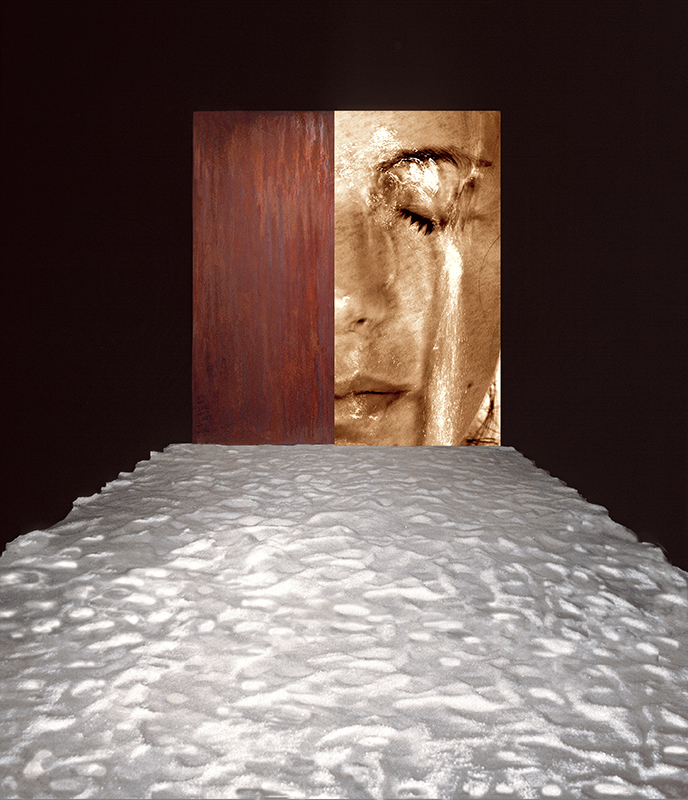

Photograph 240 x 120 cm, sheet of corroded iron 240 x 100 cm, mounted on MDF-plates, sea salt

Exhibition Art Across the Oceans, Copenhagen Cultural Capital of Europe 1996

Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art MuKHA, Antwerp