Krystyna Ziach

kunstinzicht.nlRubrieken

Over het werkFluid Time / Krystyna Ziach 2021-2023Krystyna Ziach’s Spaces of Sculptural Imagination, text by Christian Gattinoni, chief editor of lacritique.org 2015Space of Imagination / Krystyna Ziach, book, text by Hans Rooseboom, curator of photography at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2014Krystyna Ziach, Marged Disciplines, text by Hans Rooseboom, curator of photography at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2014Dark Street Revisited, 2013Work of Krystyna Ziach in collection of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2012Ephemeral Library 2010-2018Into the Void 2010-2017Inner Eye / Krystyna Ziach, by Joanne Dijkman, 2008Infinity & Archê/ Krystyna Ziach, book texts by Flor Bex, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Muhka Antwerp, 2006The Elements of Existence / Krystyna Ziach - ARCHÊ, by Cees Strauss, 1996Archê - The Ambivalence of Water and Fire / Krystyna Ziach, by Mirelle Thijsen, 1996Krystyna Ziach - Where Emotion Meets Reason, by Cees Straus, 1994A Chamber of Mirrors, text by Reinhold Misselbeck, curator of photography & new media of the Ludwig Museum, Cologne, 1994A Garden of Illusion / Krystyna Ziach, 1993, text by Iris DikOuter Space / Krystyna Ziach, text by Alexandra Noble, curator of the South Bank Centre in London,1991Melancholy / Krystyna Ziach - Drama Between Ratio and Emotion, text by Mirelle Thijsen, 1990Japan / Krystyna Ziach, by Huib Dalitz, a former director of the Foundation of Visual Arts Amsterdam, 1988Krystyna Ziach / Metamorphosis, text by Gabriel Bauret, Camera International, 1986, Paris

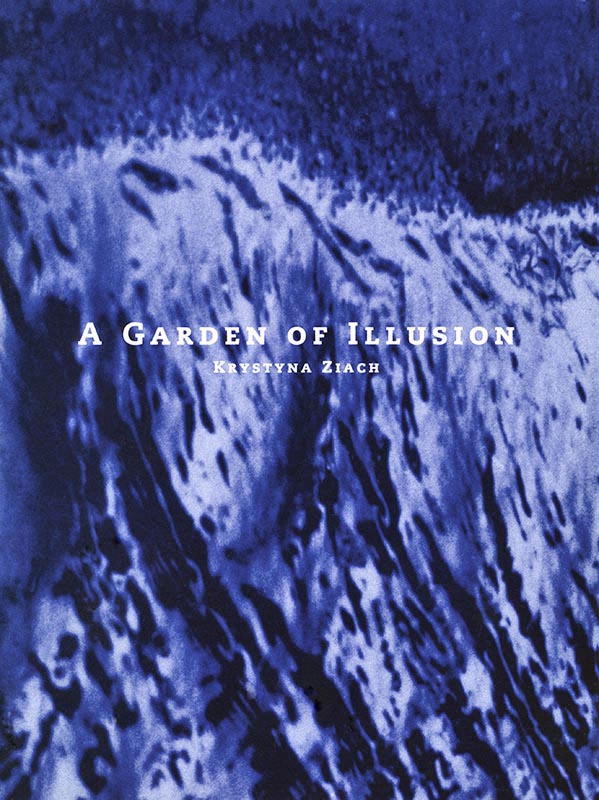

“Suppose you would take a mirror and carry it with you wherever you went. You would be able to swiftly create a sun and all that’s in the sky, swiftly an earth, yourself and the other living creatures and what’s more all matters of an artistic and natural nature”. Thus spoke Socrates in Plato’s Republic, to sustain his claim that we do not at all have to be painters to be able to imitate the world. It seems as if Krystyna Ziach took Plato’s reasoning to heart. In her new photo series A Garden of Illusion, the expressive pictorial elements which mainly characterized her photographs until now, are conspicuously absent. One also notices the absence of the photographer herself as a model and major protagonist. Instead we see ten enlarged details of simple images, printed in sepia and blue hues respectively. The photographs are set in three-dimensional geometrically-shaped frames. Within the photographs, by their side or on the floor, variously shaped mirrors are placed. Where Ziach’s earlier photo works referred mainly to the art of painting, offering a perspective on an illusionary space within the plane, now the sculptural conquest of the (exhibition) space itself has set in. Ziach gratefully uses Plato’s panacea, the mirror, not only as a mimetic, but also as a space structuring element. This development in her work comes as no surprise, given the fact that she was originally trained as a sculptress. All the photographs have been printed monochrome, five in blue and five in sepia, which is Ziach’s way of differentiating between signs of the celestial and the terrestrial, dream and reality. By this division she unites, perhaps unintentionally, two traditional meanings of the mirror in one work. Initially the mirror was the symbol for the pure truth of the divine, also used as an emblem for Maria and the angels. Later it reversely became the attribute of one of the seven cardinal sins, Vanitas (vanity). And in the hands of the goddess Venus, such as on the paintings by Rubens and Titian, it symbolizes desire. A Garden of Illusion is an artificial garden where heaven and earth, the spiritual and the sensual, reflect each other infinitely. In his lecture ‘The Nightmare’, Jorge Luis Borges narrated two of his worst anxiety dreams, in which he finds himself in a labyrinth and in a chamber of mirrors respectively. In the first dream he stands at the beginning of an infinite labyrinth. Through the cracks in the wall he tries in vain to catch a glimpse of the Minotaur in the centre. But even if he continues to walk forever, never shall he find its hiding-place. Beyond this dream of confusion and infinitude lies the second situation, where Borges is locked up in a reflecting circular room. Thus another kind of labyrinth, this time one where - reversely - he can see everything, but cannot move an inch. There the writer is confronted with himself as if he were wearing a mask. He fears that by taking off the mask his true character, or a dreadful disease, will be revealed. Krystyna Ziach’s garden of illusion is less frightening, because the observer is not a captive, but free to mirror himself in countless variations, positioned within her solid dark brown frames. Whether one may allow oneself to be seduced like Narcissus (by his ideal mirror ego), or whether one ought to search for one’s true self is not prescribed by the artist. The constantly changing spaces ‘behind the mirror’ which emerge during the walk, are related to the trompe-l’oeuil effects from the painted scenery of Ziach’s earlier photo series. Geometric forms – such as the triangle, the circle and the square - cut across each other and create continually varying connections between the separate photographic images. The photographs that Ziach used for this installation are enlarged details from shots she found in her archive, combined with photographs she took especially for the installation and which hold personal memories: a kerbstone with a puddle of rainwater in Paris, a crack in a wall, a honeycomb-like structure on a frosted glass door and a group of dilapidated houses in the Jewish quarter of Cracow. They are abstracted shots according to the technique of the blow-up, which was in vogue in the twenties with photographers such as Paul Strand and Albert Renger-Patsch, who used it to prove they could conjure up the intrinsic beauty of any trivial everyday object. Recently the exhibition ‘Minimal Relics’ showed a number of contemporary variations of this approach to photography. One could, for instance, enjoy the aesthetics of a snowball, or the traces of a human presence in abandoned industrial buildings. Krystyna Ziach’s photographs have a similar minimal appearance, but - despite the aesthetic finish - she does not seem interested in the first place in the presentation of form for the sake of form. Due to the way in which she selects and combines her images and grants them a symbolic added value, e.g. by their colour and shape, she tries to give them a new meaning by disposing of their magic in a poetic collage technique reminiscent of surrealism. The surrealistic atmosphere is enhanced by such images as a curtain, a Magrittan cloudy sky and other organic motifs such as wisps of smoke, cell structures and plant forms, in which we can project whatever inner fantasies we may have. Some photographs are plainly erotic, such as the work Illumination and the portraits of a woman in ecstasies. Ziach’s approach is more serious though when compared with the absurdism or the irony used in surrealism to create interrelations. Her photo series may be understood as a metaphysical search for the meaning of life, witness the titles of the separate works, such as A Sense of Time, Plato’s Cave, Breathing and Illumination. In a sense A Garden of Illusion is also related to a kind of alchemist’s workshop. Like the alchemists, Ziach seems to be searching for the connection between the microcosm and the macrocosm. In the imposing work Plato’s Cave, the smoke literally seems to rise up from the mirror on the floor, which brings to mind the association with purification rites. The four elements - fire, earth, air and water - return several times. As mentioned earlier, most of the photographs refer to natural materials and forms. Analogous to the way in which the laws of nature separate these elements, Ziach also graded and framed them separately. Instead of applying processes of heating and cooling, Ziach seems to use the mirror as an instrument for image distortion or amalgamation – in search for the philosopher’s stone? - until the amalgam transcends the autobiographical. On one of the mirrors one can discern a fine-grained material. Has Ziach succeeded in penetrating the essential, did she find the prima materia, or is the walk through her Garden of Illusion a mere dream, witness the blue film which lies over the powder?

Translation: Hanny Keulers

Personal catalogue, text by Iris Dik, 32 pages, published by Magazine FOTO, 1993, NL

This catalogue has been included in different libraries a.o.: Bibliothèque Kandinsky-Centre Pompidou Paris FR, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, RKD Netherlands Institute for Art History The Hague NL, MuHKA Antwerp BE and others.

Photo-sculpture, photograph, mirror, 183 x 160 cm each, diasec, wooden frames

A Diary of Desire,

6 photographs, lambda-prints, diasec, 80 x 60 cm, each

Solo Exhibition A Garden of Illusion 1992-1993

Ram Gallery, Rotterdam 1993

Photo-sculpture, photograph,180 x 127 cm, diasec, 2 mirrors, 200 x 65 cm each, wooden frames

Solo exhibition A Garden of Illusion 1992-1993

Ram Gallery, Rotterdam, 1993

Ram Gallery, 1993, Rotterdam

Solo Exhibition A Garden of Illusion 1992-1993, installation

Ram Gallery, Rotterdam, 1993