Don Satijn

kunstinzicht.nlRubrieken

Introduction to the work of Don Satijn by Inge OrlowskiBasic concepts of the work of Don SatijnLabour, harmony and meaning in the works of Don Satijn By Rutger van HoutenA concise survey of the works of

Don Satijn

By Marcel Teunissen, art historianReflections On work by Don Satijn from the series “Encryptions-Perforations”,2014-2018 By Marijke ten CaatENCRYPTIONS, by Alex HegieBarcodes by Don Satijn

An introduction to the work of Don Satijn by Inge Orlowski

«I don't get it» may be a frequent response to contemporary art in general. Viewers seem intimidated by the pressure to «get» a hidden message in an often abstract piece of art, or they altogether doubt the existence of any such message and therefore the value of the piece of art. But is it true that an artwork gets its value from its meaning and even if so, does that imply that we have to be able to understand that meaning? We tend to try to do so, of course, either by looking at the artwork itself, or by reading explanatory booklets like this one.

Understanding Art

"It is a language. […] Art is a form of communication"

It is generally acknowledged that art is a means of expression, just as language is. It would therefore have to be understandable in some way. A signifier – or example some brown and green lines and dots, or the word «tree», or the letters T-R-E-E – is linked to a signified, in this case, the mental image or the idea of a tree. In none of these cases, an actual tree has to be present. Of course, the way we will link a signifier to our mental image of what it means – in other words, how we «get» the message – differs greatly depending on the form of the signifier. The image is recognised as representing a tree because it shares common features with an actual tree through its form, maybe its colours, even though it might be two-dimensional and significantly smaller than any actual tree. If we understand the word «tree», on the contrary, this is due to no such mechanism of recognition through similarity. In language, the sign only functions on the basis of a social convention. We do not just «get» the meaning of the word from its sound. We have learned that this is what it means. The same is true for mathematical formulas. If we understand «2+2=4», it is because we have learned the meaning of each of these signs from someone else. It is al cultural code. But one way or another, when we communicate, the aim is to make ourselves as clear as possible. Or is it?

Reading a picture

The work of Don Satijn does not obey such simple rules. We see a sculpture, a painting, a print, made of canvas, cardboard, wood or steel – very classical means of artistic expression. Yet, we do not easily recognise any specific similarity to a tree, a person, or a landscape. But if we cannot recognise any shape we know of, if we cannot link this signifier to a signified, then this is no means of expression. If so – is it even art? How to link these pieces of art to something in particular?

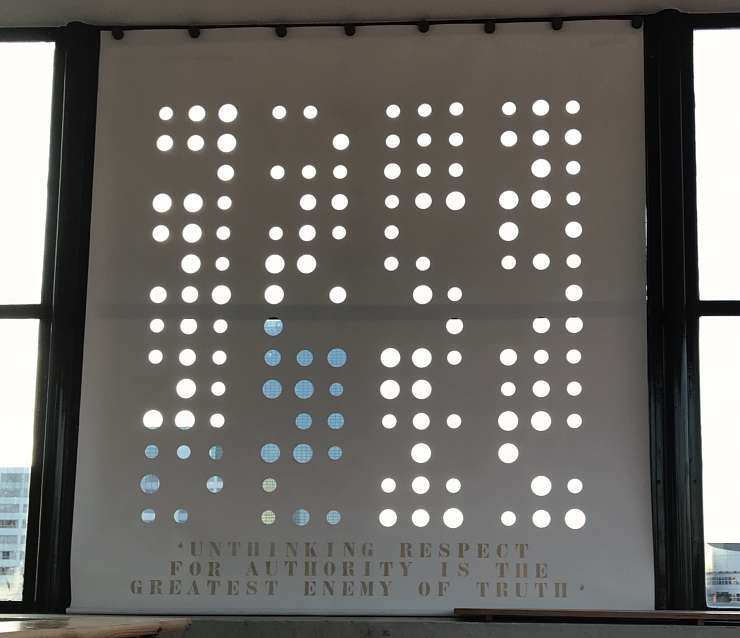

For at least some of Don Satijn's work, like the «Semiprime», the «Portraits» and the «Unthinking Respect», we could suspect that viewing them like an image, in other words looking for similarities with actual objects or scenes is not the right approach. We should much rather try to use the learned codes of language and writing. Should we, indeed, read these artworks rather than observing them? For they are readable: the numbers in the «Semiprime» have specific meanings. They are semiprime numbers, complicated and very big numbers which play a great rule in internet security, and the work also hides the birth years of the Tall Tales Company's artists. «32411» contains not only a prime numbers, but also juggling patterns. It may be read, much like a text, by a mathematician as well as by a juggler. The perforations on the «Portraits» and on «Unthinking Respect» encode the letters of the Latin alphabet. Something is written there, but in a different way than we are used to.

Having a Second Look

Not only are these things written in a way that we are not used to: they are written in a code invented by the artist. It is a writing we could not have known, and cannot decipher without the key – or a very significant amount of work. We cannot just «get» the meaning of these artworks by reading them. Indeed, the artist himself acknowledges:

"I do not expect people to decode it at all: It is almost impossible to decode! You have to have the key. Without it even for me it would take an hour to find the code"

Which puts us back on the track of the image: no, this does not resemble anything we know. At least, nothing in particular. These artworks feature abstract shapes – squares and circles – and almost exclusively black and white, in a perfection rarely to be seen in nature. The shapes are universal, which means they could represent anything. Are these stars and astrological signs? Black holes? Or a weird sort of cheese? Are the holes windows on what lied behind? Is this the pattern of drops of rain hitting a surface? Are these columns actually towers, like the huge glass buildings of our modern cities?… Once we let go of our urge to immediately understand something, we may discover whole worlds in these simple and universal shapes. An infinity of mental images none of which is more or less legitimate than the other, or, in the artists words:

"Everyone is completely free to make their own interpretation"

Is this still what we think about when we look for a meaning? Are we still linking signifiers to their signified? And is this something we would read an explanatory booklet for?

Reading the Unspoken

Yet, we must come back to the text. To the unreadable code. Because, even unreadable, it is yet present in front of us. The holes and the numbers contain it: there is a credit card number, we are looking right at it, although we do not know. There is the artists birth date. Here a prime number, and there a quote: «Unthinking respect for authority is the greatest enemy of truth». We cannot know this unless we are told so – by the title of the work, for instance, or, in this particular case, by the quote in Latin letters just underneath. If we take the time and allow our minds a similar opening movement as we did when viewing the image – is it possible that we sill be able to perceive, not the message itself, but some of its spirit? In the same way that someone hearing a totally foreign language may be entirely ignorant to what is being said, and yet be perfectly aware of the tone it is said in? Are we able to sense the mere presence of the message, even if we do not understand it, if only we open our minds beyond the want to «get it»? Is there an understanding other than by decoding?

"I believe that if something is written in a language I do not understand, the meaning is still there, like a form of energy. You can get something of it if you are open to it: not the meaning itself but something like a feeling or an energy that comes from it"

Experiencing Meaning

Semiotics is the science of how to decode signs. A famous semiotician states that language is the only sign system capable of expressing the meaning contained in other sign systems. In other words, what is shown in a picture can be said with words, but it is not always possible to sum up a text in a picture (try drawing this text, for instance). Which is why, when we want to talk about a picture, we generally resort to language rather than to another picture. The effect of the picture or the text is of course not identical, but said semiotician distinguishes between effect – which differs from one person to another – and the meaning, which is inherent to the work, and may be transcribed in language. Don Satijns art, however, challenges us to experience the meaning as an effect, as something personal that may not always be translatable to language, even though it emanates partly from a written text (e.g., the Einstein quote about «unthinking truth»). But how does the artist expect us to find our way to this kind of openness?

Looking for the Key

How does a semiotician find meaning in an artwork? They look at every element of the work and ask themselves: what else could have been here? And what does it mean that any other possible element is not there, but only the one that is? What were the other possible elements? In many of his artworks, Don Satijn drastically reduces the number of elements he chooses from:

"There is no reason to use other colours [than black and white], it is not necessary and it is not my way of expression. I keep it simple. I do not add something that would need extra explanation. A colour would raise the question of why I chose which colour"

The choice of the material the artist uses is also more often than not a practical one: for instance, big, thin sculptures would not be sufficiently stable if made out of wood, which is why they are made of steel. The artist almost seems to foresee the semioticians way of thinking. Throughout the perforation series, the semiotician need never ask: why is this dot black and not yellow or green? Yellow and green and all the other colours do not exist within the elements the artist chooses from. The semiotician need not ask: why is the hole a circle, rather than a square or an octagon? The square and the octagon are not part of the artists vocabulary for that particular series. Of course, that choice can be commented as such. But its consequence for the semiotician is that the meaning of the work is determined only by the presence or the absence of a hole, and by its size. Which narrows down the question to: what does this particular arrangement of holes in a canvas mean? Even though there are more possibilities than only zero and one, one cannot help but noticing some similarity with the binary code used by computers. In this way, Don Satijn leads the semiotician – and any viewer wanting to spend some time on reflection – very close to the truth, to decoding the encrypted text. Even though they will never succeed, they may well guess that something is, in fact, written there, that yes, this is text. This doubt, this suspicion might help us to open our minds to the text at the same time as we let them play around the image.

"Analytic ideas are interesting, because they may deepen my ways of expressing myself"

Unthinking Respect

But then again, this way of reading is only one possible approach to Don Satijns work. This is what can justify making a (semiotic) analysis of Satijns work, or reading an explanatory booklet about it: art is a means of expression, it is a language, an as such, it has to have a meaning.

"A work purely without meaning would express nothing but «this is code"

But, art does not have to be understandable, at least not in an objective way. If it were only about the message, the artist might as well have chosen to just write it down. But:

"This is the nice thing about art: the meaning is open; someone else might see something completely different. It is an open communication. I do not know whether you actually get the same message I sent. That is why I choose art: because it is open"

Art, at least that of Don Satijn, has a message, a meaning. Or even many of them, a whole universe of possible meanings. Does it have to be understandable? Well, why should we not just accept to let the artwork guide us into this journey of reading and viewing, of perceiving and reflecting. Were the message unequivocally decodable, understandable, it would make the artwork a preacher, an authority proclaiming some kind of truth. Though, «Unthinking respect for authority is the greatest enemy of truth». Art, therefore, does not need to be understandable in a conventional sense.

Sources: Titzmann, Michael: «Interaktion von Texten und Bildern». In: Titzmann, Michael und Krah, Hans: Medien und Kommunikation. Eine interdisziplinäre Einführung, Passau, 2013³.